Taxes don’t destroy farms, families do,” is posited by Dr. Steve Isaacs, professor of agricultural economics at the University of Kentucky. A provocative statement to be sure, but with a great measure of truth. A quote by Benjamin Franklin may seem an explicit anthesis to Dr. Isaacs’ statement and is the theme of this article; the quote is, “If you fail to plan, you plan to fail”. This article expands on three decisions which owners of farm businesses must answer to create an estate or business succession plan that will defend against the potential destruction and failure often caused by family dynamics.

With the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in December 2017, the estate tax exemption amount was doubled; for 2023, that amount is $12.9 million per individual ($25.6 million for married individuals). However, the exemption amount reverts to prior law and the exemption will be ~$7 million per individual starting Jan. 1, 2026. This change will increase media coverage regarding the importance of estate and succession planning for farm businesses.

Estate Planning

The Economic Research Service arm of the USDA has estimated that few farms will be subject to estate tax. For those farm businesses which will be subject to the estate tax, it will be an issue which needs to be planned for and managed. Likewise, for those farms not subject to the estate tax, planning for succession is vitally important for the continuation of the farm business. While most farms will not be subjected to federal estate tax, there are still complex questions and issues which must be addressed by these farm owners as estate and succession plans are developed. Thus, all farms and farm businesses will benefit from succession and estate planning regardless of tax implications.

When reading the Wall Street Journal or the Investor’s Business Daily, for example, there are articles which prepare the market, finance companies, banks and others for changes in firm leadership and direction. Nobody likes surprises! Why shouldn’t closely held farm businesses follow this example as well as part of the planning process?

In my experience, the mechanics of estate and succession planning are ‘relatively’ easy. While the mechanism is elegant and user-friendly, the process and three major decisions of planning are unique and challenging for each estate/transition/succession. These unique answers will create a road map for the future of each family farm business; thus, planning for transition should become a priority for the farm business.

Having a succession/transition plan in place provides landmarks to move the business forward even though there will be detours along the way. General Dwight Eisenhower stated, “…plans are useless but planning is indispensable.” This should not be taken as a discouragement, because once the plan is in play, new information will be discovered, so the plan must provide flexibility as it will not be perfect. As with much of farming, the goal is to do the best with the information available and to pivot and adapt according to new information when it’s available.

Business S Curve (or Business Life Cycle)

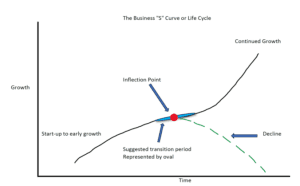

Figure 1 illustrates the Business ‘S’ Curve, or the Business Life Cycle. Growth is represented on the y-axis and time is on the x-axis. The curve begins on the lower left side of the graph, starting not at zero, but something above as human capital has value before business assets are acquired. The curve increases in scale over time and moves toward the upper right.

At some point in time, there is an “inflection point” where the curve has begun to decrease its growth; for this article, this inflection point represents new management or ownership coming into being. The point of inflection might represent death (or retirement) of the original owner and if there are successors. Are they indeed successful and follow the curve on a new upward path building upon the original owner’s foundation? Or, because of lack of planning or training, do the new owners follow the green dashed path of decline and the business fails?

The light blue elongated oval represents a transition period which is planned and managed so that new ownership can indeed succeed and follow the curve to the upper right, continuing to grow the business. This elongated oval provides sufficient time to plan for and develop answers to the three decisions. However, the farm business must be of sufficient scale and profitability to provide the opportunity for successors to achieve the potential of continued growth and ultimately economic success.

Dr. David Kohl, emeritus professor of agricultural economics at Virginia Tech, argues farm firms must grow at least at an annual nominal rate of 5% to 6% per year (2% to 3% in real terms). Thus, the firm must be profitable to accomplish this task. If the farm is not profitable, then during the time of transition, which often means multiple families are now deriving their living from the farm, cash flow and ability to meet those demands is not sustainable. The older generation and the succeeding generation may become adversaries, and hopes for succession are doomed and the farm business is destroyed.

The Three Difficult Decisions of Estate/Succession Planning

To navigate clear of failure, farm businesses must prioritize creating a flexible transition and succession plan that answers three complex decisions/questions. Additionally, it is vitally important once the plan is developed to clearly communicate that plan in some form and depth to all parties involved (family, employees, creditors and other professional service providers) to manage the element of surprise and lay the groundwork for continued farming operations into the future. Even if that communication is simply, ‘We have a plan and have done our best to be equitable.’

Within the planning process is the need to address and answer three difficult questions, which should be the priority of farms and ranches for succession to be accomplished.

Decision 1: Who Gets the Stuff

The first decision that needs to be addressed is, ‘Who gets the ‘stuff?’’ Stuff here is a very technical term; it’s the business assets, liabilities, goodwill and anything else which is of value to the business. Typically, the “who” may be the on-farm heir. However, just because the on-farm heir has the same last name as the current business owner does not indicate their qualifications for succeeding as management. If they don’t have management skills to be successful, perhaps another route is better. Off-farm heirs might be considered if their skillset and passion can be utilized to continue to grow the business. Also, from a business sustainability perspective, long-term employees may be a possibility because without their contributions, the farm business may not be where it is today.

If the current owners look at the farm through a fiduciary lens, the answer to “who gets the stuff” may be a surprise. Thus, the best model may be the farm as a “manager-managed” business with owners receiving a return on equity which may be shared with others.

Decision 2: How Do They Get the Stuff?

The second decision to be made is, ‘How do the recipients get the stuff?’ If the farm business is owned by a sole proprietor and the point of inflection in the graph represents his/her death, then the estate plan (if it exists) directs how the business assets transfer. Creating a transition plan means preparing for surprises that may arise during the reading of the will.

Long-term relationships may become damaged or strained, and relationship patterns may only become more pronounced. If a flexible plan is crafted, then land (possibly the most valuable asset) might be in a Limited Liability Company (LLC), which has explicit operating rules as well as a solid buy-sell mechanism to allow parties to exit without destroying the business. This form of business organization provides a mechanism to transfer property over time if so desired.

If the operating entity is held as a corporation, then successors acquire shares of stock through inheritance or gift. The business issue will be who has control over the operations of the business. Therefore, well-drafted language in the operating agreement(s) is required to provide the successor owner/manager(s) the flexibility to move the business forward or into a different direction. Rural areas continue to experience urban pressures, so entities with the objective of managing and limiting liability become a natural choice for farm business owners. If these entities are chosen, how ownership and management is transitioned becomes a decision of extreme importance. Like LLCs, ownership and management of corporation transfer can be accomplished incrementally by gift or in total at a sentinel event such as death of the owner.

Decision 3: When Do They Get the Stuff?

The third decision which needs careful consideration is, ‘When do the recipients get the stuff?’ In the context of Figure 1, two options are presented. The first is the point of inflection represented by the red dot. This can be upon death or retirement of the business owner. This point can be very sudden, in the case of death; or it can be planned for in the case of retirement. Everything transfers at this point, and the complete changeover may not be the best of plans.

However, the elongated oval of transition represented by the blue area provides for a period where identified successors can be prepared for the eventual full management and ownership roles of the future. An identified successor could work as an employee with a known career path reporting to the owner/manager or to another employee depending on scale of the business. It is important to have sufficient time to provide an increasing probability that the transition will be smooth with continuing support from current owners. Articles in the popular farm press discuss the need that identified successors have opportunity to grow into their future roles, and having personal investment provides incentive to develop the necessary skill set to continue the business and follow the upward trend of growth.

Presently, the window of higher estate exemption amounts may be closing as the law returns to a lower amount on Jan. 1, 2026, so estate/succession planning will become more important. The Business Life Cycle is applicable to all businesses regardless of scale (who remembers Enron?). The planning process needs to address the difficult questions facing owners of closely held farm/ranch businesses: Who gets the stuff, how will they get the stuff and when will they get the stuff? Planning for a period to identify and develop answers to these questions as represented by the blue elongated oval of transition in Figure 1 is of prime importance to transfer the business to the next generation.

Putting together a team of competent advisors to address these questions is the responsibility and obligation of farm/rancher owners in creating their plan for the future success of their business. A flexible and well-organized transition plan will act as a well-drawn road map, leading farm businesses of all sizes through inheritance and succession transitions toward growth and continued success.