A couple of things happened in 2023 that set the stage for last year’s horrible NOW year.

First, poor winter sanitation.

Second, part of the season was a lot cooler, so the first flight (spring flight) peaked about three weeks later than the previous years.

Third, hull split. It usually happens around the same time as NOW begins to emerge in second flight. In 2023, NOW emergence started about two to three weeks before the hull split and thus laid eggs in the mummies.

“We had a split population where half of NOW were found in the mummy nuts and laid eggs. The second half of the population infested the fresh nuts, and all of those emerged at the same time as a third flight because it takes a longer time for the moth to emerge from the mummy,” said Jhalendra Rijal, UCCE area IPM advisor for northern San Joaquin Valley.

“We ended up having a huge third flight peak, and that’s the one that hammered the majority of the Nonpareils as well as the pollinators,” he said.

Insecticide applications weren’t as timely in 2023 either. The coverage, hull split timing and the total duration of the split didn’t coincide at once, Rijal said.

The other issue was an uneven and protracted hull split. “Hull split is always like that, but 2023 was a particularly bad year,” he said.

“Economics was a factor too. The lower price of almonds, higher costs for winter sanitation, then unfavorable weather conditions. All of that contributed to having mummies everywhere,” Rijal said, adding there were orchards that were no or low maintenance throughout the season, likely contributing to higher NOW population.

Mating Disruption

“I like to call mating disruption an insurance policy,” Rijal said. “It’s a long-term investment where you apply mating disruption with the goal being to manage navel orangeworm properly in the long run.

“It’s even more important now because a lot of mummies currently have a lot of larvae in them. That means you can expect potentially higher pressure in 2024 too. In that case, using mating disruption helps to reduce the damage. The mating disruption research my UC colleagues and I did showed about 50% reduction in damage in almond orchards of size from 40 to 120 acres when integrated with the other currently available tools including mummy sanitation and insecticides,” he added.

Mummy sanitation is also influencing the crop grade because a lot of mummies are mixed in with the new nutmeats. If there are a lot of them, growers will have poor grade sheets and lower pricing, Rijal said.

Not investing in mating disruption and sanitation affects the crop and the bottom line, he said, although he totally understands the economic pressures that growers are facing right now.

Chemical Applications

Based on the latest work, the lepidoptera-specific products used for NOW control are still a good, solid product with good efficacy, Rijal said, and there haven’t been signs of resistance to his knowledge.

But Rijal reminds growers you can’t spray your way out of NOW. “It’s not going to work, and it’s never worked in the past. Maybe if you’re lucky one year might work, but it won’t work consistently. The insecticide is effective, but getting the insecticide to the target is the challenge, and you’ll never be able to do that unless you spray every week. The best bet is to combine all the tactics so that you will have less pressure at hull split,” he said.

Sterile Insect Technique (SIT)

Houston Wilson, an associate cooperative extension specialist in the Dept. of Entomology at UC Riverside, said the sterile insect technique (SIT) was born out of an earlier 40-year project that successfully eradicated pink bollworm using a combination of SIT, mating disruption, insecticides, crop sanitation and Bt cotton.

As part of this earlier project, a mass rearing and irradiation facility for pink bollworm was constructed in the early 1990s in Phoenix, Ariz. and operated by the USDA-APHIS. In 2018, the California pistachio industry partnered with USDA to see if they could develop sterilization techniques for NOW using this same facility, Wilson said.

“Unlike pink bollworm, the NOW SIT effort was never intended to be an eradication program. It was to develop sterile insect technique as an additional tool in the toolkit for navel orangeworm management,” Wilson said.

SIT research for NOW started in 2018. “When we were brought on to the project, they were rearing about a million moths per day,” Wilson said, adding that has since increased, and the strain of moths used at that facility has improved.

Experiments were conducted to determine the impact of transporting and releasing the moths and the impact on their performance. “By performance, I mean when we release them in an orchard, how many of them do we recover relative to wild moths, and are they able to successfully find a sentinel female and mate. And in the reverse, to see if a sterile female can attract a wild male and successfully mate.” Wilson said.

They found problems with the release methods being used, Wilson continued. So instead of just spreading the moths on a tray, we shifted to a paper grocery bag with cardboard tubes.

“By moving them to that paper bag, I think we gave them more shelter and vertical resting space, which if you think about what they’re doing on a tree, they’re resting in this vertical position,” he said.

“After we started putting them into the paper bags, we started to recover moths pretty consistently, but it remains unclear how this compares to the recovery you would expect with healthy wild moths, so we certainly still have more work to do” Wilson continued.

New Strains of Moths

A few years ago, the Phoenix facility began selecting for a different strain of moth. “Basically, what they did was they took the current existing strain, ran it through their production process, and the ones that came out healthy on the other end, they actually started breeding those to create a strain of moth that was better adapted,” Wilson said.

“We’ve run experiments over the past two years with this new strain of moth, and the recovery is about twice as high as the previous strain. And we just confirmed this past year that compared to the old strain, this new strain of moth can just as effectively mate with wild moths. Males can find wild females and the females can attract males,” he said.

SIT Research Continues

At this point, it still remains unknown if SIT will be ecologically and economically feasible, but there’s enough positive findings to merit continuing the research.

“There’s so much about the ecology of navel orangeworm that we have to better understand, like dispersal and movement between orchards. That’s a really important thing for us to know if we want to implement sterile insect technique at scale,” Wilson said, but it might come down to the cost per moth isn’t enough to to be economically viable.

Even if that happens, all is not lost because information on NOW dispersal is helpful for other management strategies like mating disruption, Wilson said.

“While the scalability of SIT remains to be seen, we continue to emphasize the use of existing strategies like crop sanitation, mating disruption and insecticides,” Wilson said. “And we continue to refine and improve those tactics as well. For instance, we’re now looking at sheep grazing for orchard sanitization, which may provide an alternative when inclement weather prevents heavy equipment or field crews from getting in to sanitize.”

In the interim, crop sanitation, mating disruption, well-timed sprays and timely harvest are critical components to NOW management, he said.

“We need to see wider adoption of some of these practices. We also want to see better regional coordination of these practices because we know navel orangeworm has a really high dispersal capacity and moves between orchards,” Wilson said. “In this way, local management efforts may be undermined if nearby orchards aren’t adequately controlling NOW.”

Carpophilus Beetle

Carpophilus beetle has been a pest of almonds in Australia for over 10 years, but nothing was found in California until late August 2023. Wilson first received a report from a PCA in Madera County in an almond orchard. After looking at the photos and inspecting nuts on-site, Wilson recognized it as carpophilus beetle and sent specimens off to CDFA, who confirmed it as Carpophilus truncatus, which is the species they’ve been dealing with in Australia over the past decade.

Almost simultaneously, Wilson received another report from a pistachio orchard in Kings County with the same signs of damage in pistachios.

“In both cases, it turned out to be carpophilus beetle,” he said.

A regional survey was then launched throughout the San Joaquin Valley and part of the Sacramento Valley to be on the lookout for the carpophilus beetle. Very quickly it was found in Stanislaus, Merced, Madera and Kings counties.

“All of a sudden, we’ve got this beetle in multiple counties. In one case, specimens were actually collected in 2022 for another project, so it seems to have been in the county for more than a year. We’re still working through our samples, and we are pretty sure we’ll come up with confirmed finds and additional counties,” Wilson said.

Wilson, Rijal and UCCE’s David Haviland will be conducting research on the carpophilus beetle in 2024.

Overwintering

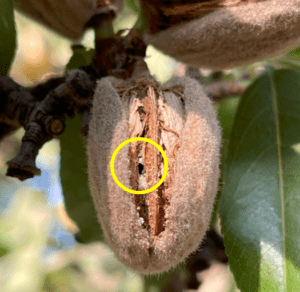

The carpophilus beetle overwinters in the remnant mummy nuts, the same as NOW, then becomes active in the spring, probably making use of those remnant nuts as a reproductive substrate, again like NOW, Wilson said.

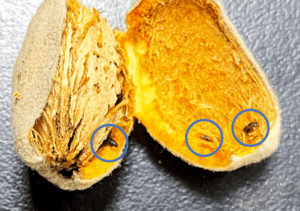

The first generation comes out of the mummies because there’s no new crop nuts for them to attack, then they go back onto those mummies until hull split. At hull split, some portion of the carpophilus beetle population moves into the new crop nuts. The adults will chew through the shell, lay their eggs inside, then the larvae develop on the kernel. The larvae leave distinctive feeding damage with an oval-shaped tunnel, plus a lot of frass and chewed up nut meat which forms a fine, white, powdery substance, Wilson said.

There are some key differences between overwintering NOW and carpophilus beetle. NOW likes to overwinter on mummies in the tree because it’s dry, off the ground, and there is less degradation of the nut. The carpophilus beetle, in comparison, seems to prefer mummies on the ground.

Chemical Controls

“What we’ve seen so far and heard from the Australians is that chemical controls are really challenging with this insect, primarily because of coverage issues,” Wilson said.Research in Australia did experiments using different spreaders, but couldn’t get consistent control. Growers there do spray, but the outcomes are really mixed, Wilson said, and mating disruption has not been developed for this beetle.

Australia has a limited set of chemistries available to them, but they’ve primarily been using bifenthrin, which is used for NOW in California.

Rijal will run pesticide trials in 2024 using insecticides that are commonly used for navel orangeworm as well as others that could be effective for the carpophilus beetle. Additionally, Rijal and Wilson are doing studies to understand the biology and ecology of this insect in California’s almond and pistachio orchards.

For now, Wilson says the take home the message for carpophilus beetle is to focus on crop sanitation, especially after 2023 with such extremely high levels of NOW infestation.

The beetle’s overwintering mortality dynamics aren’t totally understood yet, Wilson said. “We’ve really been emphasizing, when we say sanitize, we’re talking about getting the nuts out of the tree, on the ground, mow them up, maybe mow them twice. They have to be destroyed, not just resting on the soil surface.

“Don’t just give them a light disking because there was one study in Australia where they took infested mummy nuts and buried them as deep as three feet down, and even at three feet underground, the carpophilus beetle could emerge in the spring. You have to destroy these things, don’t just bury them,” he said.