Key takeaways from a report published by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) and Fresno State’s California Water Institute found water trading, smart farmland repurposing and supportive regulations should be among a few of the most crucial actions in a post-Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) California.

The report comes during a year of plentiful water thanks to a very good winter, but it also comes on the heels of years of extreme drought and expected future droughts. While the plan includes ways to bring in new supplies of water to the valley in coming years, it says 500,000-plus acres of farmland will still need to come out of intensely irrigated production.

PPIC held a live panel conference in September on the “Managing Water and Farmland Transitions in the San Joaquin Valley” report to consider how San Joaquin Valley farmers might be able to best address looming water scarcity amid future droughts while also dealing with the implementation of SGMA.

Andrew Ayres, a research fellow with the Public Policy Institute of California, presented a two-part plan to understand the opportunities and challenges of alternative land uses and what funding, incentives and institutional considerations need to be thought about to make it successful.

Water scarcity impacts by 2040 will vary across the state and come from three sources, Ayers explained: SGMA, reductions in some surface water availability from new environmental flow proposals on some tributaries in the valley, and from climate change, primarily made up of increased evaporative demands.

“All told, these cutbacks total about 20% of applied water in the valley,” Ayers said.

Water Trading

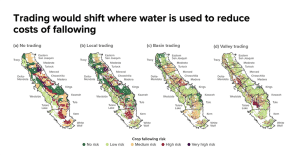

Water trading was one of the elements discussed to tackle the shortfall, and the report examines three ways water might be traded. Local trading would include growers trading surface water and groundwater in new groundwater markets with their neighbors, basin trading, which would happen within a groundwater subbasin, and valley trading, where groundwater would stay local within a basin but surface water could move throughout the valley.

“The two key takeaways are that water trading doesn’t reduce the cutbacks that need to be made,” Ayers said. “This isn’t going to reduce fallowing, but it is going to make it less costly.”

He added that across these scenarios, the total cost of adapting to the new scarcity could be reduced by about 30% to 50%. Other scenarios examined to bring water to the valley included considerations as to whether an additional 500,000 acre-feet or up to 1 million acre-feet of water could be brought in. Ayers said this method would decrease the number of cutbacks in applied water needed and the amount of fallowing, generally improving conditions in the valley.

“Being able to trade water, in some ways, spreads out the fallowing across the valley, and also it reduces the cost by allowing that water to move to the more profitable crops,” he said.

The report took into great consideration the effects water trading would have under SGMA and considered a wide range of potential impacts on the valley and its communities, Ayers said. Concerns about trading included shifts in groundwater pumping and on fallowing, which could cause undesirable impacts. Other considerations centered on drinking water levels and subsidence as well as increased dust exposure in rural communities.

“The bottom line is that managing water scarcity is a balancing act, and trading water, in practice, is tricky,” he said. “Careful design is going to be needed in the development of new groundwater markets, but trading can help reduce the negative impacts of these transitions.”

Repurposing Fallow Land

The report also examined how to repurpose fallowed land, which includes a look at solar development, water-limited crops, upland habitat, recharge basins and new housing. Of these, solar development seemed to be most promising, but only if transmission bottlenecks can be addressed. Ayers noted that even with the ambitious climate and renewable energy goals of the State of California, some projections suggest about 135,000 to 215,000 acres of land could be necessary to meet renewable energy goals.

The report’s overall recommendations also included aligning regulatory and fiscal incentives with SGMA, since many of the relevant regulations for water and land use were created long before its 2014 passage, Ayers said, adding counties will play a big role in that.

Three panels were hosted during the PPIC event. A “Managing Water in the SGMA Era” panel was moderated by Alvar Escriva-Bou, an assistant professor at UCLA, who has been working with PPIC for the past eight years. He asked panelists to weigh in on how the SGMA process is going, the goals of groundwater recharge and how they see water trading being implemented in the future.

North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) was a GSA that received a conditional pass from DWR when many others did not. Panelist Kassy Chauhan, executive officer at North Kings Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA), spoke to the successes and challenges her agency has dealt with during the plan process.

She said while it was exciting when their plan was approved, the 60-page document that gave them their approval also required some very specific corrective actions.

“The work has in some ways just begun, but we are able to continue with implementation of that plan,” Chauhan said.

She added one of the key things that made the plan successful for North Kings GSA was the fact that they held fast in their coordinated effort during the process.

Panelists Perspective

Escriva-Bou looked to longtime valley farmer Don Cameron, vice president and general manager at Terranova Ranch, Inc., for some historical perspective on groundwater issues.

Cameron, whose operation has been involved in groundwater recharge for some time, said historically, growers have felt if they owned the land, they owned the water beneath it also. Calling SGMA a game changer, he said growers have had a swing in perception and understanding.

“I just think that it’s been a real learning process, historically, a real mind-changer from what growers were used to doing in the past to really where they are today,” Cameron said.

He said he has seen a mind shift in attitude and responsibility among growers, who have been overwhelmingly supportive of helping fund solutions for continued farming within their GSAs.

“I think we have a future in California and even in some of our basins that are critically overdrafted. We’re going to find solutions,” Cameron said.

Two more panels at the event discussed land management questions that revolve around SGMA and how everyone can work together going forward.

Caitlin Peterson, PPIC Water Policy Center associate director and research fellow, said the panel she moderated, “Farmland Transitions: Where are They Now?” was about how to bring groundwater basins into balance, working on water supplies and finding ways to enhance them while reducing the transaction cost of SGMA.

As momentum builds around land repurposing, Peterson asked panelists how they’re seeing it play out day to day in their areas of expertise.

Allison Febbo, general manager for Westlands Water District, said early on they saw regulatory requirements that were reducing their water reliability and that now they’re seeing the effects of climate change and drastic weather patterns with very wet years and very dry years.

“So, our reliability, again, is not really there or predictable,” she said.

Febbo said their district so far has acquired close to 100,000 acres, which they intend to repurpose into solar and groundwater recharge opportunities.

Eric Averett, chief executive officer at Atlas Water, LLC, which works on managing large areas of land for habitat restoration, said people need to think in terms of scale when discussing land repurposing. He said when looking at land use transitions, most of the GSAs are looking to individual landowners to implement pumping restrictions, but at the same time, they aren’t coordinating at a higher level.

“As we look at land use planning and the need to fallow and transition, 40-acre parcels patchworked throughout the region doesn’t necessarily get us to where we need to be,” Averett said.

He added that their goal is to work with landowners to create incentives so they can find larger-scale plots for things like solar developments and habitat conservation flyways.

The tone of PPIC’s final panel was optimistic and focused on collaboration as the best and most productive way forward.

“In terms of collaboration, there’s no other way to do it,” said Rey León, mayor of Huron, Calif., adding climate resiliency cannot happen without social cohesion.

Karla Nemeth, director at California Department of Water Resources, said she’s feeling very optimistic.

“We’ve got this terrific history of fighting over water in California, we’re going to have that forever, but at least from my vantage point, because we now are getting more and more information about the challenge of getting these groundwater basins to a sustainable point,” she said, “it just opens up conversations we weren’t really able to have in a serious way. I think that is intensifying, and that is a good sign.”

The PPIC event video is available to watch on PPIC’s YouTube channel and the Managing Water and Farmland Transitions in the San Joaquin Valley report can be downloaded and read in its entirety on PPIC’s website.

Kristin Platts | Digital Content Editor and Social Correspondence

Kristin Platts is a multimedia journalist and digital content writer with a B.A. in Creative Media from California State University, Stanislaus. She produces stories on California agriculture through video, podcasts, and digital articles, and provides in-depth reporting on tree nuts, pest management, and crop production for West Coast Nut magazine. Based in Modesto, California, Kristin is passionate about sharing field-driven insights and connecting growers with trusted information.